The Olivet Discourse

Preface

In His famous Olivet Discourse, Jesus warned that the Temple in Jerusalem would be destroyed within the lifetime of His generation. Yet for centuries, many readers have interpreted His words—and the Book of Revelation—as descriptions of distant future events. This short book offers a clear and historically grounded alternative.

The Anglo-Christian series explores the Bible as a living record rooted in real places, cultures, and events that shaped the English-speaking world. Written in clear, accessible English, each volume is designed especially for adult readers and English learners who want to understand the Bible and its enduring moral and cultural influence on Christian thought within the Anglosphere .

This volume on the Olivet Discourse, Daniel, and Revelation continues that mission by guiding readers through some of the most misunderstood prophetic passages in Scripture, restoring them to their first-century context and demonstrating how they point not to fear of the future, but to the established and unshakable kingdom of Christ.

The Olivet Discourse in Context

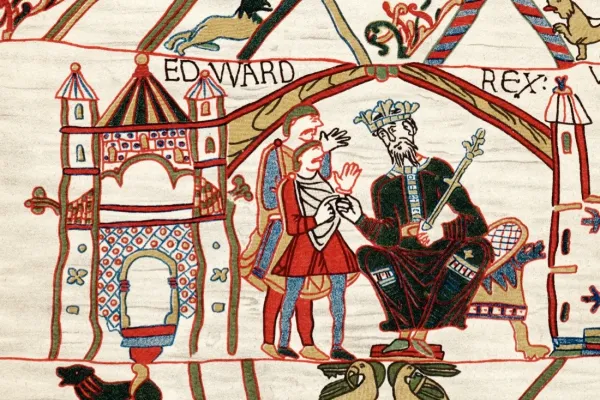

Overlooking the Temple

The Olivet Discourse is not an abstract sermon about the distant future. It is a private conversation between Jesus and His disciples, spoken in a specific place, at a specific moment, and in response to a specific question.

Jesus had just left the Temple in Jerusalem. As He departed, His disciples—like many Jews of their time—marveled at its size, beauty, and apparent permanence. The Temple was not merely a religious building. It was the visible heart of Israel’s identity, the symbol of God’s dwelling among His people, and the center of national identity.

It is precisely at this moment that Jesus speaks words that would have sounded unthinkable:

“Do you see all these things? Truly, I say to you, not one stone here will be left upon another; all will be thrown down.”

This statement frames everything that follows. The Olivet Discourse begins not with curiosity about the end of the world, but with the shocking announcement of the Temple’s destruction.

The Mount of Olives

After leaving the Temple, Jesus sat on the Mount of Olives, directly opposite the Temple complex. From this elevated position, the disciples could see the entire structure spread before them. The setting itself reinforces the seriousness of the conversation: judgment is being announced while the object of that judgment stands fully visible.

The Mount of Olives also carried prophetic significance. In the Hebrew Scriptures, it was associated with divine judgment. In the Book of Zechariah, it is prophesied that in the "day of the Lord," God will stand upon the Mount of Olives, the location for the final judgment, and the salvation of God’s people.

Jesus’ choice of location would not have been lost on His disciples, even if they did not yet grasp the full meaning of His words.

The Disciples’ Questions

The disciples respond to Jesus’ announcement with a set of closely related questions:

“Tell us, when will these things be? And what will be the sign of your coming and of the end of the age?”

Modern readers often assume these are separate, unrelated ideas. However, for first-century Jews, the destruction of the Temple would naturally signal the end of an age—the close of the old covenant era centered on sacrifice, priesthood, and the Jerusalem sanctuary.

At this point, the disciples are not asking about the end of the physical universe. They are asking about the end of their world as they know it.

Understanding this is essential. If the questions are misunderstood, the entire discourse will be misread.

“This Age” and Covenant Transition

Throughout the Gospels, Jesus speaks of two overlapping realities: the present age and the age to come. These terms do not describe the destruction of the planet, but the transition from the Old Covenant to the New Covenant.

“The people of this age marry and are given in marriage. But those who are considered worthy of taking part in the age to come and in the resurrection from the dead will neither marry nor be given in marriage, and they can no longer die; for they are like the angels. They are God’s children, since they are children of the resurrection.” (Luke 20:34–36)

The Temple represented the Mosaic system of the Old Covenant. Its destruction would mark the definitive end of the way of life that had governed Israel’s life for centuries.

Audience Matters

One of the most important interpretive principles for the Olivet Discourse is simple but often ignored: Jesus is speaking to His disciples.

He uses direct, personal language:

“When you see all these things, you know that he is near, at the very gates.” (Mark 13:29)

“Pray that your flight may not be in winter or on a Sabbath.” (Matthew 24:20)

“Truly, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place.” (Matthew 24:34)

The repeated use of “you” in the second-person plural creates an intimate, immediate tone. These statements only make sense if the events described were relevant to the people listening to Him. The discourse consistently assumes that at least some of Jesus’ original followers would live to see what He was describing.

Prophetic Imagery & Language

The Olivet Discourse belongs to a long tradition of Hebrew prophetic speech. The Old Testament prophets frequently used dramatic cosmic language to describe God’s judgment on nations. The imagery Jesus uses—such as the sun being darkened, the moon not giving its light, and stars falling from the heavens—was already familiar from the Old Testament.

Such language was commonly used symbolically to describe divine judgment on nations, and the collapse of political or religious powers. When prophets spoke of the sun being darkened or stars falling, they were describing historical upheaval in theological terms. They never intended to make literal astronomical forecasts.

Isaiah describes God's judgment on Babylon, the dominant empire of the day, by stating:

“For the stars of the heavens and their constellations will not give their light; the sun will be dark at its rising, and the moon will not shed its light.” (Isaiah 13:10)

The cosmic blackout symbolizes the total overthrow of Babylonian power—there was no literal eclipse or meteor shower.

Ezekiel used the same imagery when talking of God's judgment on Pharaoh and Egypt:

“When I blot you out, I will cover the heavens and make their stars dark; I will cover the sun with a cloud, and the moon shall not give its light. All the bright lights of heaven will I make dark over you, and put darkness on your land, declares the Lord GOD.” (Ezekiel 32:7–8)

Joel's imagery signals crisis and upheaval for Israel, not the literal end of all creation.

“The sun shall be turned to darkness, and the moon to blood, before the great and awesome day of the LORD comes.” (Joel 2:31)

When Jesus adopts this language in the Olivet Discourse, He is describing the coming destruction of Jerusalem—not a global astronomical catastrophe or the end of the physical world.

Jesus intentionally places the coming destruction of Jerusalem within the well-established prophetic tradition where poetic language of cosmic signs is used to convey the gravity of divine intervention in human history.

Before describing the specific events that precede judgment, Jesus issues repeated warnings to His disciples:

- Do not be deceived

- Do not be alarmed

- Remain watchful

- Endure faithfully

The purpose of the Olivet Discourse was to prepare Jesus’ followers for coming turmoil. It is pastoral before it is predictive. Jesus does not invite His disciples to calculate dates. He calls them to discernment, and faithfulness.

The earliest hearers of the Olivet Discourse did not possess detailed charts of the end-times. They heard Jesus as first-century Jews living under Roman occupation and suffering Jewish persecution, standing within sight of the Temple, and facing an uncertain future.

To read the discourse responsibly, we must begin where they began. Only then can we move forward—to the Synoptic Gospels, to Daniel, and eventually to the Book of Revelation—without distorting the meaning of Jesus’ words.

In the next section, we will examine how Matthew, Mark, and Luke each present the Olivet Discourse, highlighting both their shared structure and their differences.

The Olivet Discourse in the Synoptic Gospels

One Discourse, Three Witnesses

The Olivet Discourse appears in three Gospels: Matthew 24–25, Mark 13, and Luke 21. These are known as the Synoptic Gospels because they present the life and teaching of Jesus in a similar biographical way.

The presence of the discourse in all three accounts is significant. It shows that the early Christian community regarded Jesus’ teaching on this subject as essential for understanding His mission, the coming crisis, and the transition they were about to experience.

At the same time, the differences between the accounts are just as important as their similarities. Each Gospel writer shapes the material for a particular audience and purpose.

Shared Structure and Core Themes

Despite variations in wording and emphasis, the three accounts share a clear common structure:

- Prediction of the Temple’s destruction

- Warnings against deception and false messiahs

- Signs of turmoil: wars, unrest, and persecution

- A decisive moment of judgment

- A call to watchfulness and endurance

Mark

Mark’s account is widely regarded as the earliest written version. It is concise, urgent, and focused on action.

Mark emphasizes:

- Suddenness

- Suffering

- The need for endurance

“But in those days, after that tribulation, the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken… But concerning that day or that hour, no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father. Be on guard, keep awake. For you do not know when the time will come.”

“But be on your guard. For they will deliver you over to councils, and you will be beaten in synagogues, and you will stand before governors and kings for my sake, to bear witness before them… And you will be hated by all for my name’s sake.”

“But the one who endures to the end will be saved.”

The tone reflects a community already experiencing persecution. The warnings are brief and direct. Mark does not soften the intensity of Jesus’ words, nor does he expand them with lengthy explanations.

For Mark’s readers, the Olivet Discourse is not a distant prophecy. It is an urgent warning meant to be heeded.

Matthew

Matthew writes primarily for a Jewish audience. His version of the Olivet Discourse is the longest and most structured.

Distinctive features in Matthew include:

- Frequent allusions to Old Testament prophecy

- A stronger emphasis on false prophets

- Extended teaching sections, including parables about readiness and judgment

“So when you see the abomination of desolation spoken of by the prophet Daniel, standing in the holy place, then let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains.” (Matthew 24:15)

The Parable of the Sheep and the Goats in Matthew's version of the Olivet Discourse depicts final judgment, where the Son of Man separates people based on mercy shown to "the least of these my brothers" extending the discourse into an exhortation to live righteously.

Matthew places the discourse within a broader teaching framework. The destruction of Jerusalem is not merely a historical event; it is presented as part of Israel’s covenant story and Jesus’ role as its fulfillment.

Luke

Luke’s account is often the most explicit historically.

He uniquely includes references to:

- Jerusalem surrounded by armies

- The city being trampled by the nations

- A defined period of judgment on the city

“But when you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, then know that its desolation has come near. Then let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains, and let those who are inside the city depart.” (Luke 21:20–21)

"Jerusalem will be trampled underfoot by the Gentiles until the times of the Gentiles are fulfilled.” (Luke 21:24)

Luke writes for a largely Gentile audience. He is less concerned with Old Testament prophecy and more focused on explaining how these events can be clearly identified.

By describing concrete military realities, Luke removes ambiguity. What Matthew and Mark express symbolically, Luke often states plainly.

“Abomination of Desolation”

All three Gospels refer—directly or indirectly—to the “abomination of desolation,” a phrase drawn from the Book of Daniel.

Matthew and Mark preserve the phrase explicitly, assuming familiarity with Jewish Scripture. Luke, however, explains the meaning rather than repeating the term. He speaks instead of Jerusalem surrounded by armies.

This difference is crucial. It shows that the Gospel writers understood the phrase not as a mysterious future object, but as a historical reality connected to the city and the Temple.

Another shared element is Jesus’ instruction to flee.

The command makes sense only in a first-century context. Jesus does not call for rebellion, defense of the Temple, or heroic resistance. He calls for discernment and withdrawal.

This instruction was remembered and acted upon. Early Christian sources indicate that believers left Jerusalem before its destruction, taking Jesus’ warning seriously. Church historians describes this as the flight to Pella. Pella, a city east of the Jordan River, offered a safe refuge beyond Judea’s borders, away from the Roman siege and the escalating violence within Jerusalem. The flight to Pella shows that His disciples took the Olivet Discourse not as abstract eschatology for a distant future in a distant land, but as urgent, life-preserving guidance for their generation.

When read together, the Synoptic accounts reinforce one another. Mark provides urgency, Matthew provides theological depth, and Luke provides historical clarity.

None of the accounts point readers toward a distant end-of-the-world scenario detached from their own time. All three are anchored in the looming crisis facing Jerusalem and its people.

Understanding these complementary perspectives prepares us for the next step: tracing how Jesus’ language draws deeply from the Old Testament—especially the Book of Daniel.

In the next section, we will examine those Old Testament foundations and explore why Daniel is essential for understanding the Olivet Discourse.

Old Testament Foundations of the Olivet Discourse

Jesus as a Prophet Within Israel’s Scriptures

Jesus did not speak in a theological vacuum. His language, imagery, and warnings in the Olivet Discourse are deeply rooted in a long prophetic tradition within the Hebrew Scriptures. Isaiah used prophetic imagery and language to describe the fall of Babylon. Ezekiel applied it to Egypt. Joel employed it in the context of judgment upon Israel. For His original listeners, Jesus' prophetic imagery and language would not have sounded foreign, mysterious, or exaggerated. It would have sounded precise, meaningful, and historically grounded—echoing how earlier prophets described divine judgment on nations and covenant unfaithfulness.

Daniel

Among all Old Testament books, Daniel stands at the center of the Olivet Discourse. Daniel is unique because it addresses the rise and fall of empires, persecution of God’s people, the vindication of the faithful, and the transfer of authority from earthly rulers to God’s chosen king.

Jesus explicitly refers to Daniel when speaking of the “abomination of desolation”:

“So when you see the abomination of desolation spoken of by the prophet Daniel, standing in the holy place (let the reader understand)…” (Matthew 24:15)

This is not a minor reference. It signals that Daniel’s visions provide the interpretive lens through which the entire discourse should be read.

The Son of Man

One of the most misunderstood elements of the Olivet Discourse is Jesus’ reference to the “Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven”:

“Then will appear in heaven the sign of the Son of Man… they will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven with power and great glory.” (Matthew 24:30)

This phrase comes directly from Daniel 7:

“I saw in the night visions, and behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him; his dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away…” (Daniel 7:13–14)

In that chapter, the Son of Man does not descend to earth. He approaches the Ancient of Days and receives authority, glory, and a kingdom. The movement is upward, not downward. Daniel’s vision describes enthronement and vindication following suffering—not a physical return to earth. When Jesus applies this imagery to Himself, He is claiming that the coming judgment on Jerusalem will publicly confirm His authority and kingship, transferring dominion from the old covenant order to the everlasting kingdom inaugurated through Him.

Daniel and the Judgment on Jerusalem

Daniel 9 speaks of a determined period leading to the end of sacrifice and the desolation of the holy city:

“…and the anointed one shall be cut off… and the people of the prince who is to come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary. Its end shall come with a flood, and to the end there shall be war. Desolations are decreed… And on the wing of abominations shall come one who makes desolate, until the decreed end is poured out on the desolator.” (Daniel 9:26–27)

The focus is not a distant global catastrophe, but the consequences of covenant unfaithfulness—cessation of temple worship and judgment on Jerusalem. Jesus’ language in the Olivet Discourse closely parallels Daniel’s themes:

- judgment focused on Jerusalem

- the cessation of temple-centered worship

- a decisive historical moment bringing an era to its close

Rather than inventing new prophecy, Jesus declares that Daniel’s words are reaching their fulfillment in the events His generation would witness.

Daniel & the Gospels

Daniel 12 describes a period of unparalleled distress, followed by deliverance for God’s people:

“At that time shall arise Michael, the great prince who has charge of your people. And there shall be a time of trouble, such as never has been since there was a nation till that time. But at that time your people shall be delivered, everyone whose name shall be found written in the book.” (Daniel 12:1)

Jesus echoes this language when He speaks of a “great tribulation”:

“For then there will be great tribulation, such as has not been from the beginning of the world until now, no, and never will be.” (Matthew 24:21)

Once again, the context is crucial. In Daniel, the distress concerns the fate of Israel—not the end of the physical universe. The emphasis is on covenant crisis and resolution. Jesus reassures His followers that this period, though severe, will be limited. It will not continue indefinitely. By invoking Daniel, Jesus anchors His warning firmly in Israel’s story and signals the fulfillment of covenantal prophecy.

This trajectory continues in the Gospels. Judgment is real, but it is not the final word. Authority passes to the Son of Man, and the faithful are called to perseverance.

This Old Testament foundation prepares us for the next question: if the Olivet Discourse is so deeply rooted in Daniel, why does the Gospel of John omit it entirely?

In the next section, we will explore that question and begin tracing the path from the Olivet Discourse to the Book of Revelation.

John’s Gospel

The Missing Olivet Discourse

Readers familiar with Matthew, Mark, and Luke often notice something striking when they turn to the Gospel of John: the Olivet Discourse is missing.

There is no extended teaching on the Mount of Olives. No detailed discussion of the Temple’s destruction. No list of signs or warnings comparable to the Synoptic accounts.

This absence is not accidental. John is not unaware of the Olivet Discourse. Instead, his Gospel reflects a different purpose, audience, and stage in the life of the early church.

John Writes Last—and Writes Differently

Most scholars agree that John’s Gospel was written later than the Synoptics. By the time John wrote, the core events of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection were already well known among Christian communities, and the Synoptic accounts had circulated widely.

John himself acknowledges this selective approach:

“Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of the disciples, which are not written in this book; but these are written so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name.” (John 20:30–31)

He adds in the epilogue:

“Now there are also many other things that Jesus did. Were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written.” (John 21:25)

John does not repeat what is already widely taught. He complements it.

Where the Synoptics emphasize Jesus’ public teaching in parables, John focuses on extended theological discourses. Where the Synoptics stress chronology and narrative flow, John emphasizes meaning and identity—Jesus as the divine Word incarnate, the one who reveals the Father perfectly.

Rather than repeating Jesus’ warnings about coming judgment, John emphasizes themes that explain the theological significance of that judgment:

Jesus as the true Temple

In the temple cleansing episode, Jesus declares:

“Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.”

The Jews respond,

“It has taken forty-six years to build this temple, and will you raise it up in three days?”

But John explains:

“But he was speaking about the temple of his body. When therefore he was raised from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this, and they believed the Scripture and the word that Jesus had spoken.” (John 2:19–22)

The physical Temple fades into the background, replaced by Christ Himself—His body as the place where God dwells with humanity:

“the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” (John 1:14)

Jesus as the fulfillment of Israel’s feasts

John structures much of Jesus’ ministry around the Jewish festivals, showing Him as their true fulfillment. For example, at the Feast of Tabernacles:

“On the last day of the feast, the great day, Jesus stood up and cried out, ‘If anyone thirsts, let him come to me and drink. Whoever believes in me, as the Scripture has said, “Out of his heart will flow rivers of living water.”’ (John 7:37–38)

And at the same feast:

“I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.” (John 8:12)

These declarations position Jesus as the living reality behind the feasts' shadows.

Jesus as the final revelation of God

John presents Jesus as the ultimate disclosure of the Father:

“No one has ever seen God; the only God, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known.” (John 1:18)

And to Philip:

“Whoever has seen me has seen the Father.” (John 14:9)

In John’s Gospel, the physical Temple fades into the background, replaced by Christ Himself. The question is no longer where God dwells, but in whom He dwells.

This shift makes a separate Olivet Discourse unnecessary. Although John omits the extended prophetic warnings about Jerusalem's fall, he does not avoid the theme of judgment. Jesus speaks repeatedly of the coming of an “hour”, judgment already beginning, and light exposing darkness.

Jesus anticipates His passion and glorification as the decisive "hour":

“The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified… Now is my soul troubled. And what shall I say? ‘Father, save me from this hour’? But for this purpose I have come to this hour. Father, glorify your name.”

“Jesus knew that his hour had come to depart out of this world to the Father”

Judgment is not merely future but inaugurated in Jesus' ministry:

“For the Father judges no one, but has given all judgment to the Son… Truly, truly, I say to you, an hour is coming, and is now here, when the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live.” (John 5:22, 25)

Judgment is tied to the arrival of light:

“And this is the judgment: the light has come into the world, and people loved the darkness rather than the light because their works were evil. For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed.” (John 3:19–20)

These statements assume the same theological framework as the Synoptics but express it differently. Judgment is portrayed as both imminent and already unfolding through Jesus’ ministry—His presence forces a decision, exposing unbelief and inaugurating the new covenant era.

The absence of the Olivet Discourse in John's Gospel prepares the way for its expansion in the final book of the New Testament, the Book of Revelation. In this book, John returns to the themes of judgment, vindication, and kingdom—but now through visions, symbols, and imagery deeply rooted in Daniel and the prophets.

To understand Revelation, we must first understand what John assumes his readers already know.

In the next section, we will turn directly to the Book of Revelation and explore how it functions as John’s expanded and symbolic continuation of the Olivet Discourse.

Revelation as John’s Olivet Discourse

Revelation

The Book of Revelation is often read as though it stands apart from the rest of the New Testament. It is treated as a mysterious appendix, disconnected from the Gospels and largely inaccessible without specialized knowledge.

In reality, Revelation belongs firmly within the same theological and prophetic stream as the Olivet Discourse, but develops Jesus’ teaching. What Jesus spoke in plain prophetic language overlooking Jerusalem, John presents in symbolic visions to churches around the ancient world.

Written to Real Churches in a Real Crisis

Revelation opens with letters addressed to seven historical churches in Asia Minor (Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, Laodicea). These communities were facing uncertainty about their future. They suffered persecution from Jewish communities, and pressure to compromise under Roman imperial demands for emperor worship.

John repeatedly emphasizes the immediacy of the message:

“The revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave him to show to his servants the things that must soon take place.” (Revelation 1:1)

“Blessed is the one who reads aloud the words of this prophecy, and blessed are those who hear, and who keep what is written in it, for the time is near.”

“the Lord… has sent his angel to show his servants what must soon take place… Blessed is the one who keeps the words of the prophecy of this book”

“Do not seal up the words of the prophecy of this book, for the time is near.”

These statements make little sense if Revelation is primarily about events thousands of years in the future. They make perfect sense if the book addresses the same covenantal transition announced by Jesus in the Olivet Discourse—judgment on the old order (including Jerusalem's fall in AD 70), the vindication of Christ’s people amid persecution, and the inauguration of Christ's kingdom amid ongoing trials.

Revelation echoes the Olivet Discourse in both structure and emphasis:

- Warnings against deception (e.g., “Beware of false prophets” in Matthew 24:11 parallels Revelation's false teachers and the "false prophet" in Revelation 19:20; 20:10).

- Persecution of the faithful (e.g., Revelation 2:10: “Do not fear what you are about to suffer… Be faithful unto death, and I will give you the crown of life.”)

- False prophets and false messiahs (e.g., the "beast" and "false prophet" in Revelation 13:11–18, echoing warnings of false christs in Matthew 24:24).

- Calls to endurance and watchfulness (e.g., Revelation 13:10: “Here is a call for the endurance and faith of the saints”; Revelation 14:12: “Here is a call for the endurance of the saints, those who keep the commandments of God and their faith in Jesus.”)

- The vindication of Christ and His people (e.g., Revelation 19:11–16 depicts Christ as conquering King, echoing the Son of Man's vindication).

The difference lies in presentation. Jesus spoke directly to His disciples. John writes symbolically to protect, encourage, and strengthen churches living under Jewish and Roman persecution—using coded imagery that Roman authorities would not easily decode.

Just as the Olivet Discourse draws heavily from Daniel, Revelation is saturated with imagery from Daniel. Beasts, horns, thrones, time periods, and heavenly courts all appear repeatedly. Revelation does not invent new symbols; it intensifies and reuses existing ones.

For example, the Beast from the sea:

“And I saw a beast rising out of the sea, with ten horns and seven heads… It was allowed to make war on the saints and to conquer them.” (Revelation 13:1, 7)

This echoes Daniel 7:

“I saw… four great beasts… and it had ten horns… a horn… made war with the saints and prevailed over them.” (Daniel 7:7–8, 21)

Where Daniel looked forward to the transfer of authority to the Son of Man, Revelation announces that this transfer has begun. The Lamb stands at the center of heaven, already enthroned, already victorious.

The figure of the Beast in Revelation has generated endless speculation. Yet its function closely parallels the enemies described in Daniel and the Olivet Discourse. The Beast represents persecuting power opposed to Christ and His people—demanding loyalty that belongs to God alone. For first-century believers, this imagery was immediately recognizable as the Roman imperial cult of emperor worship, and did not require detailed explanation.

Just as Jesus warned His disciples to endure tribulation:

“the one who endures to the end will be saved.” (Matthew 24:13)

Revelation calls believers to endure tribulation as witnesses:

“They have conquered him by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony, for they loved not their lives even unto death” (Revelation 12:11).

One of Revelation’s central images is the fall of a great city characterized by wealth, power, violence and opposition to God’s reign—Babylon:

“Fallen, fallen is Babylon the great! … For all nations have drunk the wine of the passion of her sexual immorality, and the kings of the earth have committed immorality with her.”

This imagery resonates strongly with Jesus’ warnings about Jerusalem and the Temple. Judgment is portrayed not merely as destruction, but as exposure—the unveiling of corruption.

Revelation presents judgment as both historical and theological. Events on earth reflect realities already decided in heaven.

Revelation repeatedly affirms that Christ reigns now:

“Jesus Christ the faithful witness, the firstborn of the dead, and the ruler of kings on earth.” (Revelation 1:5)

“The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ, and he shall reign forever and ever.” (Revelation 11:15)

The kingdom announced by Jesus in the Gospels is inaugurated and made unshakable in Revelation. The Olivet Discourse warned of coming judgment. Revelation assures believers that this judgment is part of God’s redemptive plan, where Christ is vindicated, and His people are preserved.

To read Revelation apart from the Olivet Discourse is to read it without its proper guide. Jesus provides the framework. Daniel provides the imagery. John assures believers that judgment is imminent and just. When Revelation is read this way, it ceases to be a source of speculation and becomes what it was always meant to be: a revelation of Jesus Christ.

In the next section, we will consider an often-overlooked truth: the first followers of Jesus did not understand every prophetic detail, yet they followed Him faithfully—and that reality continues to shape how Revelation should be read today.

Faith Without Full Understanding

The Limits of the First Followers’ Understanding

One of the most overlooked features of the Gospels is how little Jesus’ closest followers understood while they were following Him.

The disciples misunderstood Jesus’ mission repeatedly. They argued about status, expected political victory, and failed to grasp the meaning of His suffering—even after He spoke of it plainly:

“From that time Jesus began to show his disciples that he must go to Jerusalem and suffer many things from the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised. And Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him, saying, ‘Far be it from you, Lord! This shall never happen to you.’” (Matthew 16:21–22)

Yet Jesus did not wait for complete understanding before calling them to follow. Faith preceded comprehension.

The first disciples followed Jesus without knowing how Old Testament prophecies would be fulfilled, that the Messiah would suffer and die, and that the Temple would be destroyed within their lifetime.

“They still did not understand from the Scripture that he must rise from the dead.” (John 20:9)

“They understood none of these things. This saying was hidden from them, and they did not grasp what was said.” (Luke 18:34)

They trusted the person of Jesus long before they could interpret the meaning of events. This pattern continues throughout the New Testament.

Parables and the Concealment of Wisdom

Jesus often taught in parables, explaining that this was intentional:

“To you it has been given to know the secrets of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it has not been given… This is why I speak to them in parables, because seeing they do not see, and hearing they do not hear, nor do they understand… For this people’s heart has grown dull, and with their ears they can barely hear, and their eyes they have closed, lest they should see with their eyes and hear with their ears and understand with their heart and turn, and I would heal them.” (Matthew 13:11, 13, 15; quoting Isaiah 6:9–10)

Parables reveal truth to those willing to hear and conceal it from those who are hardened. They are not puzzles designed to reward cleverness, but moral and spiritual filters.

Understanding, therefore, is not merely intellectual. It is ethical.

This principle applies equally to the Olivet Discourse and to Revelation. Both reveal Christ to those willing to hear and conceal it from those whose hearts are hardened.

The Thief on the Cross

Few passages illustrate faith without full understanding more clearly than the account of the thief on the cross.

One criminal railed at Jesus, but the other rebuked him:

“Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed justly, for we are receiving the due reward of our deeds; but this man has done nothing wrong.”

And he said:

“Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.”

Jesus replied to him:

“Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise.” (Luke 23:40–43)

The criminal possessed no theological system, no prophetic framework, and no opportunity for moral reform. He simply recognized Jesus’ innocence and entrusted himself to Him. Jesus’ response is immediate and unqualified.

Revelation Is Not a Test of Orthodoxy

Throughout church history, believers have disagreed deeply about the meaning of Revelation. Yet the New Testament never presents correct interpretation of apocalyptic imagery as a measure of faithfulness. Revelation was given to encourage perseverance in the first century, not to divide believers into those who understand and those who do not more than two thousand years later.

Its central message is clear even when its symbols are not: Christ reigns, evil will not prevail, and Jesus responds to those who have faith in Him.

Faith Guards Against Pride and Speculation

The New Testament calls believers to have faith in Jesus, not to have a complete comprehension of every detail of scripture. In fact, not knowing should guard against pride, and speculation.

John himself models this approach in Revelation. He does not explain every symbol, nor does he encourage his readers to decode them exhaustively.

Instead, he repeatedly calls for patient endurance, faithfulness under pressure, and refusal to compromise allegiance.

“Here is a call for the endurance of the saints, those who keep the commandments of God and their faith in Jesus.” (Revelation 14:12)

“Be faithful unto death, and I will give you the crown of life.” (Revelation 2:10)

“Hold fast what you have, so that no one may seize your crown.”( Revelation 3:11)

Revelation assumes that partial understanding is sufficient when faith is genuine.

What God Chose to Reveal

Scripture distinguishes between what God has revealed and what He has not.

Jesus explicitly states that some knowledge belongs to the Father alone:

“But concerning that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but the Father only.” (Matthew 24:36)

“It is not for you to know times or seasons that the Father has fixed by his own authority.”

This is not a failure of revelation, but a protection for faith. God reveals only what is necessary for trust, obedience, and hope. The danger of apocalyptic literature lies not in mystery, but in misplaced curiosity. When curiosity becomes the goal, faithfulness suffers. When faithfulness becomes the goal, mystery becomes manageable. Jesus did not tell His disciples everything they wanted to know. He told them everything they needed to know.

The Olivet Discourse, Daniel, and Revelation all point beyond themselves. They do not ask readers to trust timelines, charts, or systems. They ask readers to trust a King. Faith that rests in Christ does not depend on full prophetic clarity. It depends on confidence that God is faithful, present, and sovereign.

In the next section, we will return to history itself and examine how the Olivet Discourse was understood and fulfilled in the generation that first heard it.

The Fulfillment of the Olivet Discourse in History

Returning to Jesus’ Words

Jesus’ warnings were not abstract principles detached from real events. They were specific predictions addressed to a particular generation. If the Olivet Discourse was fulfilled, it must be traceable within the historical record. If it was not, Jesus’ credibility would be called into question. The question, therefore, is not whether history matters, but whether we are willing to take it seriously.

Following Jesus’ death and resurrection, tensions in Judea intensified.

Jewish resistance to Roman rule grew steadily. Political unrest, messianic movements, and internal divisions weakened the region. Ancient historians record frequent uprisings, false deliverers, and violent confrontations—precisely the conditions Jesus warned about:

“You will hear of wars and rumors of wars… Nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom” (Matthew 24:6–7).

Far from being exaggerated, the language of the Olivet Discourse proves restrained when compared with the chaos that followed.

Luke records Jesus’ warning in unmistakably concrete terms:

“But when you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, then know that its desolation has come near. Then let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains…” (Luke 21:20–21).

In 66 AD, Roman forces initially advanced but withdrew unexpectedly, creating a brief window. Over the next several years, Jerusalem was increasingly isolated, besieged, and starved as Titus (son of Emperor Vespasian) led a full Roman campaign. The city that symbolized God’s covenant presence became the focal point of judgment.

Early Christian sources indicate that believers heeded Jesus' warning to flee when the decisive moment arrived, leaving Jerusalem before the final siege. Rather than perishing with the city, they escaped to surrounding regions.

Eusebius of Caesarea in his Ecclesiastical History states they left Jerusalem for the town called Pella. Pella, in the Decapolis east of the Jordan, provided safety beyond Roman lines. This historical detail is crucial. Jesus’ instructions were not symbolic gestures; they functioned as practical guidance that preserved life. No early sources record Christians dying in the siege.

The suffering during the siege of Jerusalem was extreme. Ancient accounts, especially Flavius Josephus in The Jewish War (an eyewitness Jewish historian who defected to Rome), describe famine, internal violence, and widespread death. The breakdown of social order was complete. Families turned against one another. Religious leadership collapsed.

Josephus details the horrific famine that reduced people to desperation: one woman, Maria of Perea, roasted and ate her own infant son amid starvation. He writes of the city filled with “horrid action” and people preferring death to continued misery, with bodies piling up so thickly that the ground was invisible. Internal factions (Zealots, Idumeans, and others) fought viciously, plundering food stores and weakening defenses further.

Jesus’ description of:

“great tribulation, such as has not been from the beginning of the world until now, no, and never will be” (Matthew 24:21)

was not rhetorical exaggeration. It reflected the reality of a city consuming itself—famine more terrible than slaughter, as Josephus notes many preferred Roman mercy to the horrors within.

In 70 AD, the Roman army under Titus destroyed Jerusalem and burned the Temple on the the same date as the Babylonian destruction centuries earlier.

The Temple’s destruction marked the definitive end of the sacrificial system. No further sacrifices could be offered. The heart of the old covenant order ceased to function.

Jesus’ words were fulfilled with devastating precision:

“Do you see these great buildings? There will not be left here one stone upon another that will not be thrown down.” (Mark 13:2)

Josephus describes the Temple's utter ruin: Roman soldiers tore it down stone by stone to recover melted gold, leaving massive rubble heaps at the Temple Mount base—archaeological evidence still confirms widespread toppling of stones.

One of the most debated phrases in the Olivet Discourse is Jesus’ statement that:

“this generation will not pass away until all these things take place” (Matthew 24:34).

When read in light of historical fulfillment, the meaning is clear. The events unfolded within the lifetime of those who first heard Jesus speak—a single generation. The historical record confirms the plain sense of Jesus’ words.

For early Christians, the destruction of Jerusalem was not a cause for triumphalism. It was a sobering confirmation of Jesus’ authority. The judgment vindicated Jesus as a true prophet and Messiah. It also confirmed the transfer of covenant identity away from the Temple and toward Christ Himself.

The fulfillment of the Olivet Discourse demonstrates a crucial distinction. An age ended. A covenantal order passed away. But the world did not. History continued. The church expanded. The gospel spread far beyond Jerusalem. Jesus’ words accomplished exactly what they promised—no more and no less.

For believers, the events of 70 AD are not merely historical data points. They are theological testimony. They confirm that God acts within history, and that Jesus’ words are trustworthy.

In the next section, we will explore how early Christian writers understood these events—and how later interpretations gradually shifted away from historical fulfillment.

Early Christian Interpretation of the Olivet Discourse and Revelation

The Earliest Readers

After the destruction of Jerusalem, early Christians were forced to interpret what they had witnessed. The Temple was gone, the city lay in ruins, and Jesus’ words had been dramatically confirmed.

How did the earliest Christian writers understand the Olivet Discourse and the Book of Revelation? Rather than speculating about distant futures, they reflected on recent events and their theological meaning. Their interpretations are valuable not because they are infallible, but because they stand closest to the world of the New Testament.

Early Christians had seen Jerusalem fall. They had witnessed persecution, upheaval, and the end of the Temple system. Jesus’ warnings were not puzzles awaiting solution, but explanations for events already endured.

As a result, early interpretation focused less on prediction and more on confirmation: Jesus had spoken truthfully, and God had acted decisively within history.

The anonymous author of the Epistle of Barnabas written in the late 1st or early 2nd century treats the Temple's destruction as fulfillment of Jesus' prophecy and the end of the old covenant system. He writes:

“For the Scripture says concerning him [the Messiah]: ‘He will make a new covenant with us… and the old one he has abolished.’ Therefore the temple of the Lord is truly spiritual.” (Barnabas 16:6–8, paraphrasing Jeremiah 31 and linking to the new covenant inaugurated in Christ).

For the author, the physical Temple's ruin confirmed that God had shifted His dwelling from the physical temple to the spiritual community of believers.

In the mid-2nd century Justin Martyr repeatedly connected the Olivet Discourse to 70 AD, viewing the destruction as divine judgment:

“For the prophecy of Isaiah… was fulfilled in the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans… and the desolation of the land.” (Dialogue 52).

He also sees Christ's kingdom as present reality:

“The eternal kingdom of the same Christ has been already announced, and His power is already manifested.” (Dialogue 32).

Justin reads Revelation's imagery as describing Christ's current reign and victory, not a postponed future.

In the late 2nd century Irenaeus anchored much of Revelation in the first-century context, affirming the Olivet Discourse's fulfillment in the Temple's fall:

“The abomination of desolation… was fulfilled when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem.” (Against Heresies 5.30.4, linking Daniel and Matthew 24).

He emphasizes Christ's present authority:

“The Son of God… reigns now in the midst of His enemies.” (cf. his use of Psalm 110 and Revelation 5).

In the early 4th century Eusebius of Caesarea, writing after Constantine, explicitly ties the Olivet Discourse to 70 AD as historical fulfillment:

“These things happened to the Jews… in exact accordance with the predictions of our Saviour.” (Ecclesiastical History 3.5.4–6, referencing the flight to Pella and the siege).

He stresses the inaugurated kingdom:

“Christ has already begun to reign… the kingdom is not of this world but spiritual.” (Demonstration 3.2).

Early Christian teaching consistently affirmed that Christ’s kingdom had already begun. Jesus was confessed as reigning at God’s right hand. His authority was not postponed until a distant future, but exercised in the present.

This conviction shaped how early believers read both the Olivet Discourse and Revelation: judgment had occurred (on the old covenant order), the kingdom had been inaugurated, and history was moving forward under Christ’s rule.

As time passed and the destruction of Jerusalem receded into memory, and interpretation gradually shifted. Later generations, further removed from the original context (especially after the 4th–5th centuries), began to read the Olivet Discourse and Revelation less historically and more futuristically. What had once been remembered as fulfilled prophecy became imagined as events yet to come.

In the next section, we will examine how later futurist interpretations developed, how repeated failed fulfillments shaped modern prophecy culture, and why a return to historical grounding is both necessary and healthy today.

Futurism, Failed Fulfillments, and Doomsday Christianity

The Rise of Futurism

As the memory of Jerusalem’s destruction faded (especially after the 4th–5th centuries), Christian interpretation of prophecy began to change. What earlier generations remembered as fulfillment later generations increasingly treated as expectation. The Olivet Discourse and Revelation were gradually detached from their first-century context and relocated into an undefined future.

Futurism approaches prophetic texts as primarily unfulfilled, locating their meaning almost entirely at the end of history. Under this approach time indicators such as “soon,” “near,” and “this generation” are reinterpreted to mean thousands of years or are dismissed as being purely symbolic while the historical facts relating to Jerusalem and the Temple are ignored or minimized.

The result is a reading that prioritizes speculation over context and anticipation over remembrance. Once prophecy is pushed into the future, it becomes vulnerable to constant reapplication. Throughout history, various movements have confidently identified their own generation as the final one. Wars, plagues, political figures, and technological developments have all been presented as definitive signs of the end.

In the 2nd century Montanists claimed the New Jerusalem would descend in their day, leading to mass disappointment when it did not occur.

In the 12th century Joachim of Fiore predicted the “Age of the Spirit” would begin in 1260, with the Antichrist appearing soon after—none of which materialized.

In the 16th century, many Reformers and Anabaptists saw the papacy as the Antichrist and the Reformation era as the prelude to Christ’s return—yet the world continued.

In 1844 William Miller calculated Christ’s return for October 22, 1844, leading thousands to abandon faith or form new groups when the date passed.

In the 20th century, Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth (1970) tied Revelation to 1980s events (e.g., European Common Market as the ten-horned beast, Soviet Union as both the Beast and Gog/Magog); many expected the rapture by 1988 (40 years after Israel’s founding); when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 without apocalyptic fulfillment, new charts were drawn, and timelines were adjusted.

Today, many link the European Union, barcodes, microchips, AI, or specific political leaders or global events (e.g., certain U.S. presidents or Middle East figures) to the Antichrist or “mark of the beast,” only for predictions to fail repeatedly. Yet new applications continue to emerge.

The outcome has been consistent: dates pass, predictions fail, but Doomsday-focused interpretations continue to evolve. Nevertheless, at their core they remain the same. History is viewed as a countdown to collapse, anxiety replaces hope, withdrawal replaces engagement, fear replaces faith, leading some to live in constant dread avoiding long-term commitments in anticipation of imminent tribulation.

Another consequence of futurist interpretation is the creation of interpretive elites. Those who claim special insight into prophetic timelines (through charts, seminars, or “secret knowledge”) gain authority over others. Scripture becomes a tool for control rather than encouragement.

In some modern contexts, prophecy has shifted from pastoral guidance to religious entertainment. Books like the Left Behind series (1995–2007) sold over 80 million copies by portraying Revelation as a dramatic thriller with airplanes crashing and global chaos. Symbolism is flattened into spectacle—high-tech beasts, global conspiracies, and cinematic rapture scenes—capturing attention and generating revenue, but rarely producing maturity or faithfulness.

One of the clearest indicators of interpretive instability is the constant adjustment of meaning. When predictions fail, interpretations are revised rather than abandoned. Fulfillment is always imminent but never arrives.

The “generation” that sees Israel’s rebirth was once said to be 40 years, then 70 years, then “this generation” was redefined as an indefinite period. Antichrist candidates shift from Napoleon, Hitler, Stalin, to U.S. presidents—each time the “proof” is reinterpreted after failure. The “beast” and “mark” have been applied to everything from Nero to the Pope to credit cards to vaccines—each time the system is updated when the previous identification fails.

This pattern contrasts sharply with Jesus’ own approach, which anchored prophecy to a defined generation in Jerusalem:

“Truly, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place.” (Matthew 24:34)

When prophecy repeatedly fails, the credibility of the Christian message suffers. Outsiders associate faith with sensationalism rather than truthfulness. Insiders grow disillusioned or cynical—some leave the church altogether, feeling betrayed by unfulfilled promises.

A historically grounded reading of the Olivet Discourse and Revelation does not deny the future. The New Testament does not end with terror, if understood correctly it replaces panic with confidence, and obsession with faith. Prophecy occupies an important place in Scripture, but it was never meant to dominate Christian life. Worship, love, endurance, and hope remain central.

In the final section, we will bring these themes together by reflecting on the nature of the kingdom of heaven—established, unshakable, and not dependent on future catastrophe.

The Kingdom of Heaven

Jesus’ Central Message

From the beginning of His ministry, Jesus proclaimed one central reality:

“The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel.” (Mark 1:15)

This announcement did not refer to a distant political future or the eventual collapse of the world. It declared that God’s reign was arriving decisively through Jesus Himself.

The New Testament consistently speaks of the kingdom as both present and enduring. Jesus described it as already among His listeners, growing quietly like a mustard seed, and advancing without spectacle.

“The kingdom of God is not coming in ways that can be observed… for behold, the kingdom of God is in the midst of you.” (Luke 17:20–21)

“The kingdom of heaven is like a grain of mustard seed… which indeed is the smallest of all seeds, but when it has grown it is larger than all the garden plants and becomes a tree…” (Matthew 13:31–32)

“The kingdom of God is as if a man should scatter seed on the ground… and the seed should sprout and grow, he knows not how.” (Mark 4:26–27)

The apostles echoed this understanding, speaking of Christ as reigning at God’s right hand and of believers as already belonging to His kingdom:

“He has delivered us from the domain of darkness and transferred us to the kingdom of his beloved Son.” (Colossians 1:13)

“You are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession…” (1 Peter 2:9)

The kingdom was not postponed.

Not an Earthly Political Empire

A frequent misunderstanding arises when the kingdom of heaven is equated with an earthly political system. Jesus explicitly rejected this expectation. He refused political power, and declined to lead rebellion.

“When Jesus perceived that they were about to come and take him by force to make him king, he withdrew again to the mountain by himself.” (John 6:15)

“My kingdom is not of this world. If my kingdom were of this world, my servants would have been fighting…” (John 18:36)

His kingdom does not rise through force or legislation. It advances through faith and transformation—changed hearts, renewed lives, and faithful witness.

This distinction explains why the kingdom could be fully established without overthrowing Rome—and why it continues to grow without needing to replace modern governments.

The destruction of Jerusalem marked the end of the old covenantal order and confirmed the authority of Christ. Judgment cleared the ground for a kingdom not tied to one city, one temple, or one ethnic identity. What was shaken passed away. What could not be shaken remained:

“Yet once more I will shake not only the earth but also the heavens… Therefore let us be grateful for receiving a kingdom that cannot be shaken…” (Hebrews 12:26–28)

Revelation does not end with annihilation, but with renewal. The final vision is not escape from creation, but restored communion between God and humanity:

“Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God. He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more…” (Revelation 21:3–4)

If the kingdom of heaven is already established, believers are not tasked with predicting collapse or accelerating the end. They are called to have confidence in Christ’s reign as it transforms fear into trust, panic into perseverance.

The Place of Prophecy

Daniel, the Olivet Discourse, and Revelation occupy an important place in Scripture—but not the whole place. They are given to strengthen hope, confirm God’s faithfulness, and encourage endurance. When read in proportion, they illuminate Christ rather than overshadow Him.

The final message of Scripture is not fear of what is coming, but confidence in what has already been established. The Olivet Discourse warned of judgment. Daniel revealed the coming kingdom. Revelation unveiled the reigning Christ. Together, they testify to one unchanging truth:

“The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ, and he shall reign forever and ever.” (Revelation 11:15)